Engineering

– 11 min read

Beyond vibe coding: prototyping enterprise agents

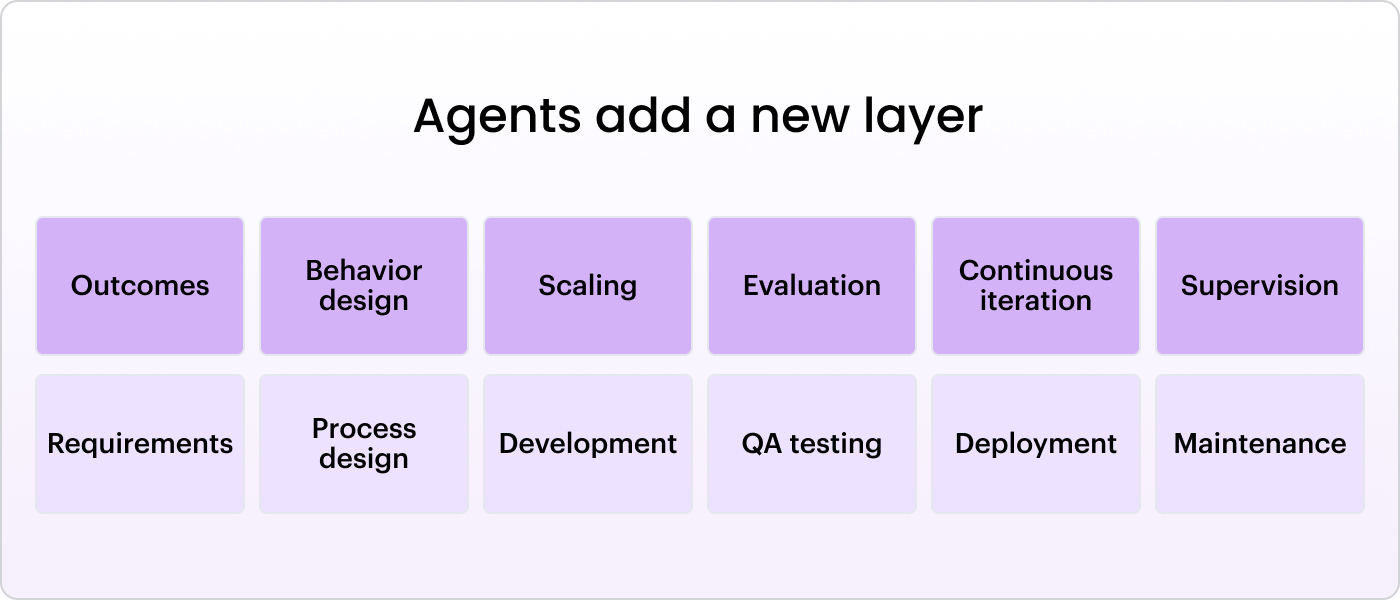

Deterministic code rules don’t apply. The Agent Development Lifecycle (ADLC) starts with rapid prototyping that drives clarity on what you’re building before you commit to code.

Traditionally, building software inside the enterprise could be a long, winding process. Software teams have known for decades that time-to-value is the hardest KPI to hit. The Standish Group’s CHAOS Report shows only 31% of projects ship on time and on budget, while 50% blow past both, and 19% get canceled outright — burning capital without creating value.

These lengthy timelines are partially because, in the traditional software development lifecycle (SDLC), the people who understand the workflow best usually aren’t the ones building the solution. They help write requirements, hand them off, and get looped back in to test the MVP, often when it’s too late to course-correct.

AI is breaking that paradigm. With tools like Cursor, Lovable, and Replit, anyone can describe what they want to build and generate working code in minutes. Suddenly, business teams aren’t just proposing ideas, they’re creating prototypes you can see, click, and iterate on.

But in the enterprise, prototypes only get you so far. Use cases are messy, with legacy system integrations, complex custom logic, and strict security and compliance requirements. You can’t “vibe code” your way into production. As Gartner notes in their research on no-code agent builders, “unrestrained AI agent development by workers will lead to agent anarchy, including conflicting automations, security gaps, and increased operational risk.”

At WRITER, we’ve seen this pattern again and again while helping Fortune 500 teams build their first agents. That’s why we’ve codified the Agent Development Lifecycle (ADLC) — a practical approach for delivering agents that actually work at an enterprise scale.

When you code up a new software tool or feature, you are crafting the logic. The steps it takes are deterministic, and the inputs and outputs are usually fixed. The beauty of an agent is that it can take the powerful intelligence of today’s AI models and work to achieve outcomes on your behalf, adapting its behavior to use different tools or approaches, responding to changes in available data, and making decisions about how to alter course or try new tactics to get to the desired outcome.

Just like modern software starts with vibe coding, our approaches to building have flipped the traditional sequence on it’s head — instead of starting with specs and docs, build a prototype, learn what works, and then invest in longer-term development (for the developers and IT leaders reading this, don’t lose your cool just yet. We’re not eliminating these best practices — we’re simply adding a layer to them.

This is the first post in our ADLC series, starting where every successful agent begins: prototyping. In our methodology, prototyping consists of defining the agent outcomes, designing its behavior, and building a simple proof-of-concept.

The rise of the Agent Owner

The key to effective prototyping is treating it as a tool to drive alignment between business and technical teams rather than as a throwaway demo.

Prototypes force ideas into the real world. They expose functionality you didn’t know you needed, systems that don’t talk to each other, and clunky features that are unintuitive to use — all before a single line of code gets written.

Of course, most employees don’t have the time, motivation, or technical fluency to prototype complex workflows, and they shouldn’t have to. They’re better off spending their energy on the deep work that requires their domain expertise. So, who actually should build these prototypes?

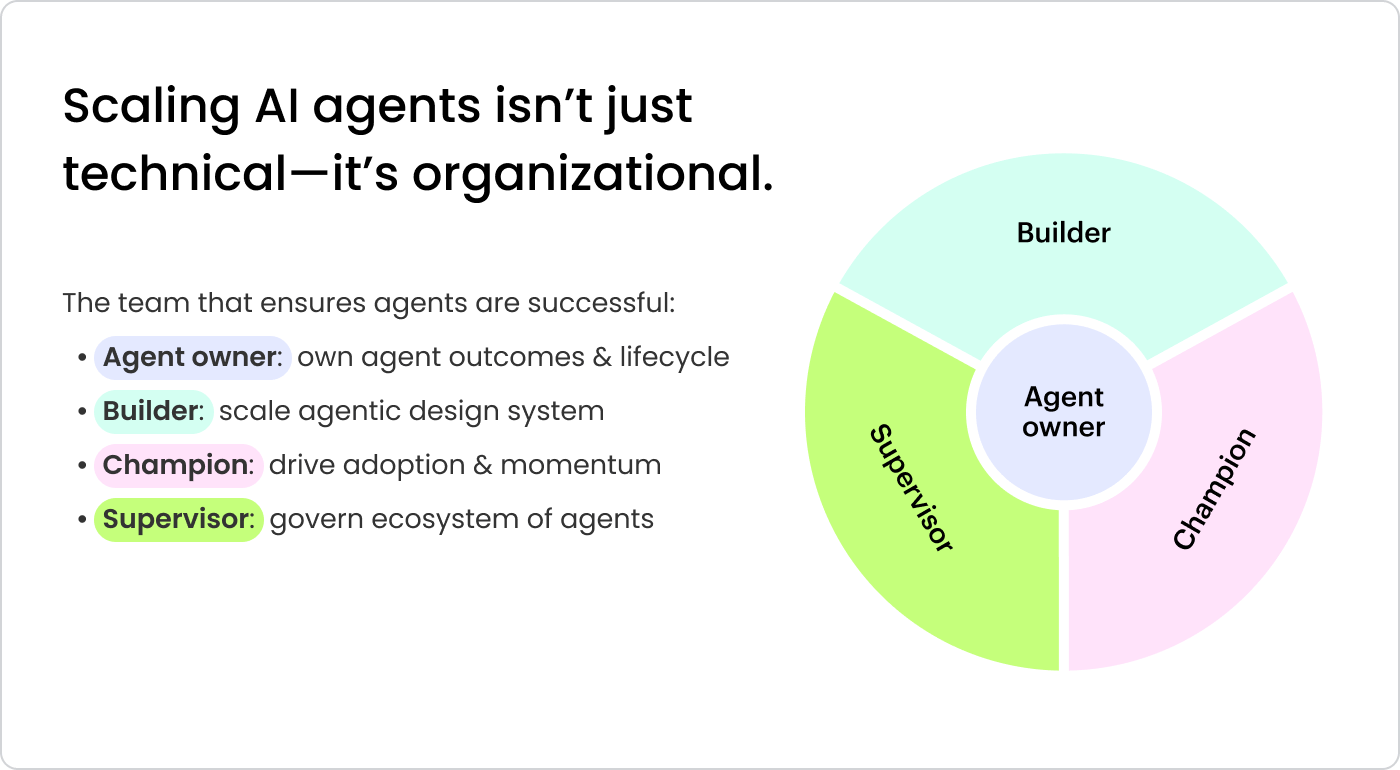

As we’ve worked with enterprise customers on agents, we’ve seen the emergence and evolution of four key roles in the ADLC:

- Agent Owners act like systems PMs. They align agents to business goals and drive iteration.

- Builders focus on scale, robustness, and integrations. They build reusable templates, orchestration logic, and secure systems.

- Champions drive internal adoption and promote best practices across teams.

- Supervisors monitor behavior, ensure reliability, and manage trust and safety across the agent ecosystem.

In the prototyping phase, the Agent Owner is critical.

Agent Owners define what an agent is responsible for, ensure it delivers measurable business outcomes, and stay accountable for iteration:

- They’re systems thinkers with strong instincts for process design and configuration, often already tinkering with low-code or no-code tools.

- They’re deeply embedded in the business and understand how work actually happens, but they’re also technical enough to collaborate effectively with engineering.

- Operational excellence is their full-time mandate, not a side hustle. They drive accountability from idea to outcome and don’t abandon projects when they hit friction.

- They often sit in digital transformation, innovation, or business operations teams (like Marketing Ops or GTM Ops) that already own key processes and systems.

As the driver of prototyping, Agent Owners sit at the intersection of business champions — who know what “good” looks like — and technical builders and supervisors — who bring it to life as a reliable, production-ready agent.

The enterprise guide to prototyping agents

Once you’ve defined the Agent Owner who will drive the prototyping process, you’re ready to begin — but hang on, don’t jump straight to vibe coding. The best prototypes don’t start with a prompt — they start with a plan. Scoping upfront gives your agent the structure it needs, so your first prompt isn’t a shot in the dark and you get to a working prototype faster.

The goal is to start high-level and set strategic direction, then progressively layer in detail to ground the prototype in reality:

- Map the Process: Break down how the work gets done, step by step, system by system

- Define the outcome: Anchor the prototype to a real business goal and a measurable result.

- Scope the job: Outline what the agent needs to do and who it’s for.

- Prototype: Bring it to life in an interactive demo to test assumptions and gather feedback.

Step 1: Define the outcome

First, get clear on why you’re building in the first place.

If you can’t explain the business outcome in one sentence, you’re already failing. Start with the metric that keeps someone awake at night, like customer support response time, contract review bottlenecks, or compliance report generation. Then ask — What does success look like in numbers? Not “better” or “faster,” actual numbers. “Reduce ticket resolution by 30%” is much more likely to lead to the creation of a successful agent than “Make ticket resolution time faster.”

We worked with a client whose legal team was drowning in contract reviews. Instead of building “an AI legal assistant,” we focused on one outcome: reducing initial contract review time from four hours to 90 minutes. That clarity shaped every technical decision we made. We built a single-purpose agent that extracted key terms and flagged potential issues, and it worked because we knew exactly how to measure success.

Vague mandates lead to scope creep, feature bloat, and projects that limp along for months without shipping. Clear outcomes lead to systems that get deployed, adopted, and improved. And when it comes time to evaluate performance, having that measurable outcome makes it clear “what good looks like” and how to optimize towards it.

Step 2: Scope the job

Once you have defined the outcome, clearly delineate the job to be done. A well-scoped agent isn’t just an executor — it’s a teammate with a clear mission and outcome to own. Anchor your scope in these elements:

- Users: Who’s involved in the workflow? Set the scene with their role and responsibility, and consider who takes action, who approves, and who just needs visibility.

- Process: What’s the usual sequence of steps, and when does it happen? Keep it simple, with just enough detail so someone can understand the flow of work. You’ll map the full process in the next step.

- Systems: What tools or platforms are involved? List the systems the agent might need to access or interact with, like CRMs, ticketing systems, or analytics platforms.

- Knowledge: What context does the agent need to do its job effectively? Think about what documentation or data a new team member would need to get onboarded.

- Deliverables: What artifacts get created in the process? Are they docs, spreadsheets, decks, reports, or something else? Be specific and consider the audience. Instead of “campaign report,” say “quarterly brand campaign report for the marketing executives.”

Step 3: Map the process

Once you’ve scoped the job, it’s time to break down the process into the actual flow of work.

Don’t just list steps — design for how the work actually happens. Blend deterministic execution (what must happen) with non-deterministic logic (what changes based on input, context, or judgment). Be precise where accuracy matters, but stay open-ended where adaptability adds value. That’s how you create agents that are both reliable and creative.

For each step in the flow, define the following:

Triggers: The events or signals that set the agent in motion. An agent can have multiple triggers if it needs to respond to different scenarios:

- User-initiated: When a person takes action, like submitting a form or clicking a button

- System events: When a system gets updated, like a new lead created in CRM

- Scheduled: When a timed cadence occurs, like “run every day at 9am”

- External signals: When a real-world change is detected, like a stock price volatility spike or a breaking news alert about a competitor

Owner: The individual responsible for taking action. Make sure to consider the level of human oversight required based on the risk, complexity, or judgment involved:

- Agent: The step is fully automated and doesn’t require human review. Best for low-risk, repeatable tasks or outputs that can be reviewed later, like summarizing meeting notes.

- Human-in-the-loop: The agent executes, but human approval is needed to continue. Best for when trust is still being built, like drafting a customer reply.

- Human: The person executes the task. Best for anything that requires nuance, carries liability, or involves strategic judgment, like making a hiring or budgeting decision.

Inputs: The specific context needed to complete the step. Look back at what you scoped in the “Knowledge” and “Systems” sections and add another layer of detail:

- Source: Where the input comes from, whether it gets added by a user as an upload, included if a system event is triggered, or drawn from a previous step.

- Format: Structured (JSON, form fields) or unstructured (freeform text, docs) and any pre-processing required to make it usable, like reformatting data or converting a file type.

Output: The result of the step. This could be a final deliverable or something used in a later step, like a research summary used to generate a slide deck.

- Destination: Where the output is delivered or stored, whether it gets surfaced in a chat window, sent in Slack, dropped into email, or saved in a system.

- Format: Whether the output must follow a specific structure, like CSV instead of Excel, Notion instead of Google Docs, plain text instead of a formatted Gmail draft.

Guardrails: Boundaries that constrain the agent’s behavior. They define what’s off-limits, what policies must be followed, and how to stay aligned in edge cases or ambiguity.

- Rules: Hard limitations that the agent must follow, like always masking PII data or limiting web searches to trusted domains.

- Thresholds: Conditional limits on actions, like “Always escalate requests over $10,000 to a manager”

- Policies: Organizational, legal, or brand guidelines the agent must respect, like voice or regulatory requirements

Step 5: Prototype

Finally, it’s time to put all the pieces together into your first prompt for the vibe coding platform of your choice. Don’t worry about hooking up systems, memory, or knowledge sources just yet — the goal is to prototype a clickable demo that helps work through the flows.

To start, give the LLM just enough to scaffold the agent’s behavior without overwhelming it. Use what you scoped in Step 2 to draft a prompt like this:

##Instructions

You are prototyping an AI agent. The goal is to demonstrate the agent’s end-to-end workflow using sample data. The prototype does not need live integrations, but it should illustrate behavior clearly. If the required context is missing, ask for clarification before proceeding.

## Goal

Persona: You are a growth marketer whose job is to track the performance of campaigns.

Outcome: Reduce weekly campaign reporting time to under 30 minutes.

## Process

1. Retrieve last week’s campaign data from Google Analytics every Monday at 9am PT.

2. Compare actuals to goals (CTR, CVR, spend, ROI).

3. Flag any campaigns that underperformed.

4. Draft suggested actions (e.g., pause, A/B test, adjust targeting).

5. Output a formatted summary in Google Doc for marketing lead review in Slack.

## Knowledge

– Campaign performance data from Google Analytics.

– Campaign goals overview from Google Sheet.

## Deliverables

– Google Doc with analysis.

– High-level summary of campaign performance.

– Table of flagged campaigns with issue and metric.

– Recommended next step per underperformer.

– Slack message with key highlights.

## Guardrails

– Do not suggest changes to campaigns with <3 days of data.

– Flag low-confidence recommendations (<75% confidence) for human review.

– Use a clear, neutral tone — never assign blame.

Refine the Slack message output to be more skimmable and easy to edit.

– Include a one-line TL;DR at the top (max 140 characters).

– Use emoji bullets for readability (e.g. 📉, ✅, 🔍).

– Provide an “Edit message” text box so a user can make changes.

– Include a “Send to Slack” button so a user can easily send.

Apply these rules to the final campaign report:

– Do not suggest changes to campaigns with <3 days of data.

– Flag low-confidence recommendations (<75% confidence) for human review.

– Use a clear, neutral tone — never assign blame.

Once your prototype reflects the overall flow of your agentic process, you’re ready to use it to align with stakeholders before building the production agent.

What comes next

Prototyping is the fastest way to pressure-test your direction, surface blind spots, and get everyone aligned before you invest in the real build.

In the next piece in our Agent Development Lifecycle (ADLC) series, we’ll dive into what it takes to turn your initial prototype into a production-ready agent.

Ready to bring ADLC to your team? Book a demo to learn how we help enterprises move from prototype to production faster.

Looking to get hands-on? Dive into our docs to start building, or try prototyping with Action Agent, WRITER’s general-purpose autonomous agent.

Gartner, 3 Impacts of No-Code Agent Building in the Digital Workplace, Jason Wong, Keith Guttridge, 24 June 2025