Thought leadership

– 7 min read

The orchestration graph

Why execution is free, supervision is expensive, and the firm must be rewired

When the constraint changes, so does the firm

Firms have always been shaped by their constraints.

Labor was expensive. Coordination was difficult. Execution required time, teams, and overhead. These limitations didn’t just influence how companies operated, they defined why they existed, how they structured themselves, and what strategy looked like in practice.

We built the enterprise in the image of its bottlenecks. However, with the rise of AI agents, one of the most fundamental constraints – execution capacity, is rapidly dissolving.

Employees equipped with fleets of synthetic agents can now operate with 10x leverage. Tasks once requiring teams can be handled solo. Execution runs continuously, on demand, at near-zero marginal cost.

So the real question isn’t what firms optimize for in a world of abundant execution, it’s:

- What happens to structure, to resourcing, to how success is measured

- How firms operate when a foundational constraint disappears

The firm still matters, but its center of gravity shifts

In 1937, Ronald Coase described the firm as a way to reduce transaction costs. When contracting tasks out to the market was too expensive or risky, companies brought them in-house: hiring employees, building hierarchies, and managing workflows internally.

That explanation held up for decades. And in many ways, it still does. Firms remain valuable because they bundle:

- Institutional memory: deep context about products, customers, and operations

- Shared norms: how decisions are made, what quality looks like

- Governance infrastructure: escalation paths, accountability, control

This is especially true for incumbents. Market leaders have amassed not just capital, but coordination capacity. The invisible muscle that lets thousands of people move in relative unison.

But that muscle is no longer the center of gravity.

As AI systems make execution and coordination programmable, the firm’s role evolves. It no longer exists primarily to perform work. It exists to orchestrate the doing of work, routing objectives across a mesh of agents, humans, and hybrid systems.

The firm becomes less like a factory and more like an operating system: a platform for managing distributed, intelligent execution.

And as orchestration becomes software defined, triggered by workflows, prompts, and APIs then the line between “inside the firm” and “outside” begins to blur. What once required headcount can now be handled by models-as-a-service. What once required departments can now be composed from agentic primitives.

What once required an in-house analytics team might now be handled by an LLM-powered insight agent subscribed via API.

The next generation of firm strategy will hinge on redrawing these boundaries:

- What work must remain in-house to protect quality, context, or IP?

- What work can be delegated to external orchestration layers, partner agents, or API-based execution models?

It’s not just a tooling shift, it redefines what the firm actually contains.

Coordination Is now programmable

In the traditional enterprise, coordination was manual. Calendars, Slack, middle managers. Getting things done meant pushing information through people. In the hybrid enterprise, coordination becomes programmable.

Agents can talk to each other. They can follow escalation logic, retry on failure, adapt to changes in real time. A well-designed prompt becomes a living SOP. A constellation of agents becomes a distributed operating unit.

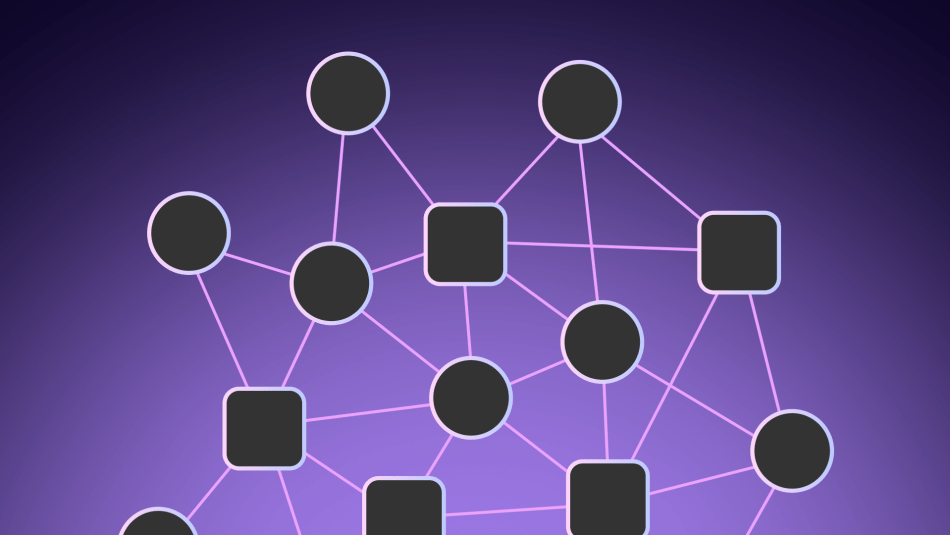

This reframes the org chart. It’s no longer the primary map of how work flows. The orchestration graph is: the dynamic, often invisible network of people, agents, and systems connected by delegation logic, execution loops, and escalation paths.

Designing a modern company means designing that graph. Not who reports to whom, but what gets routed where, under what supervision, and with what degree of autonomy.

For example, a modern product team might include a single PM working alongside a network of agents: one auto-prioritizes bugs from support data, another drafts PRDs based on Slack threads and customer interviews, a third runs roadmap simulations to detect delivery risk. None of this coordination happens in meetings or planning docs. It happens through orchestration logic, defined in workflows, automation rules, and natural language triggers.

Which means firm design becomes system design:

- What gets delegated to agents

- When humans step in

- How output is validated

- How the system learns over time

Not: “Who manages whom?”

But: “How do we route work across this human-machine network, and how do we supervise it at scale?”

Productivity isn’t an output metric – It’s a system diagnostic

If orchestration becomes the new coordination layer, then what we measure must evolve with it. Productivity is no longer a count of actions, it’s a signal of how well a system is functioning.

In many cases, the person is no longer producing; they’re designing the system that does.

A Product Manager might launch ten experiments in a week without writing a single ticket – because they’re managing agents that generate briefs, build flows, analyze results, and deploy iterations.

Their value isn’t in activity, it’s in throughput yield from the system they orchestrate.

So productivity becomes a diagnostic for system performance, not human effort:

- Was the orchestration efficient?

- Were agents used appropriately?

- Were human escalations necessary? Timely? Avoidable?

- How did the system improve over time?

New metrics emerge:

- Time to delegate: how long it takes to route work to the right execution layer

- Synthetic throughput per employee: how much work their agent systems produce

- Escalation-to-resolution ratio: how often supervision is required, and how well it’s handled

These metrics aren’t vanity, they’re vital. Because when humans are supervising synthetic labor, your system is your team.

And that system must be supervised, not merely observed, like any high-performance machine with both human and synthetic parts. This isn’t about logging or telemetry. It’s about enabling hybrid teams to act with confidence, trust, and control at scale.

In the post-scarcity firm, the most productive employees aren’t the busiest, they’re the ones whose systems generate the highest throughput per unit of supervision.

Supervision becomes the cost of scale

In this new world, the cost structure shifts: Execution is cheap. But supervision is expensive.

When the marginal cost to deploy agents is zero, why wouldn’t you? But without oversight, agents can drift, misfire, or act out of bounds. And when agents act at scale, small errors compound into large failures, fast.

So in the hybrid enterprise, supervision becomes the new constraint.

This isn’t people management in the traditional sense. It’s a new form of operational control:

- Designing safe delegation paths

- Configuring guardrails and permissions

- Auditing agent behavior

- Allocating human attention where it matters most

Costs don’t reappear in labor – they reappear in maintaining confidence. Confidence that the system will act reliably, escalate when needed, and improve over time.

Supervision becomes an economic primitive:

- It gates what work can be delegated

- It determines which systems are safe to scale

- It defines where performance bottlenecks actually lie

That means firm-level decisions like resource allocation, org design, operating models must be optimized for supervised scalability, not headcount.

The constraint has moved. The structure must follow.

The rewiring of the enterprise

The core constraint of the modern firm is shifting: From labor to leverage. From execution to orchestration. From headcount to confidence.

As synthetic capacity becomes cheap and abundant, the firm’s role is no longer to internalize execution. Rather, it’s to ensure the orchestration graph functions safely and effectively. It’s to route, supervise, and evolve the system that does.

Org charts no longer reflect the true structure of the company. The real shape of the firm is the orchestration graph, a dynamic network of humans, agents, tools, and rules, connected by delegation and escalation paths.

Strategy becomes systems design. Management becomes supervision. Productivity becomes throughput yield.

The companies that thrive in this new era won’t be the ones that scale headcount fastest. They’ll be the ones that adopt the orchestration graph as their new operating model, redefining how work is structured, supervised, and scaled.

The firm isn’t disappearing. It’s just being rewired.