AI agents at work

– 17 min read

How to build an AI-native marketing engine: The platform capabilities that make it possible

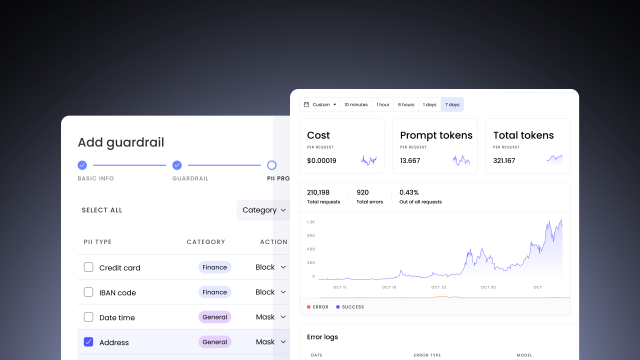

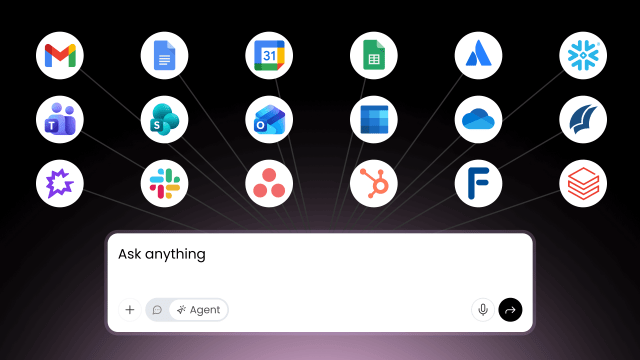

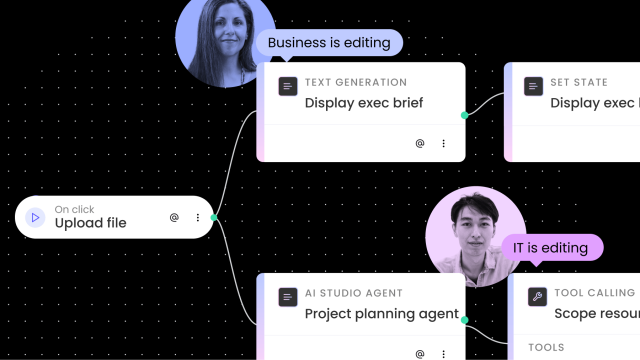

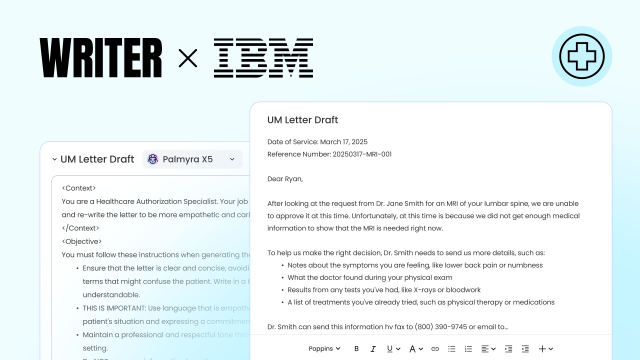

Most marketing teams are stuck in AI pilot mode. Learn the 5 platform capabilities—from multi-step orchestration to enterprise governance—that separate 10-20x transformation from marginal gains.